We get to choose what it is we want to focus on. Which story to tell about ourselves and the world around us. One full of abundance, possibility, growth, and choices or one that is scarce, fixed, and limited. In the end, we get what we hope for. Each of us is in search of meaning in our lives. We can’t fill it with materials. No matter how hard we try it won’t fill our cups. Sure, we can distract ourselves but in the depths of our hearts, we know better. No one wants to feel like a rat on the wheel that is constantly spinning or someone who just keeps pulling the lever at a slot machine. Perhaps, the only antidote to consumption, the cancer in our culture today, is creation. Either way, the only meaning we can derive is the one we choose. If you are optimistic in this approach, you will more likely find what it is in your search than the pessimistic person. We hide from this by saying, “I am just trying to be real.” But reality is but a perception. The world comes at us through wavelengths, the eyes then translate that image to our brain for us to see. In fact, we perceive the world after it has already happened. What is reality then anyway? We don’t even know where we are. A spec of dust in an infinite galaxy. Being real is a moment of real clarity that we only experience in special moments. Most of the time, we are insulating ourselves from reality. And that’s okay. Because reality bites. The path forward, however, is dealing with the tension of seeing things as they are while having hope for things to get better.

Surveys in places like Britain and Holland reveal that nearly 40% of all workers are convinced that their jobs make no meaningful contribution to the world. Another 13% say they are not sure. This means that about half of the workforce thinks their job is necessary while the other half believes it is pointless. If you think about it, a janitor at a hospital can say I am helping patients and the doctors stay clean. The car mechanic helps other people get to work. The teacher teaches future generations the skills they need to thrive. How do 4 out of 10 people working jobs feel that if their jobs suddenly disappeared overnight it would either make no difference or make the world a better place. So, who are half the people who think their job has no meaning?

The Bullshit Job, as David Graeber has defined it, is a job so pointless that the person doing it believes it shouldn’t exist and you can’t admit it out loud to anyone. We have been indoctrinated since the rise of industrialism that work is part of what it means to be productive. So far as to say that any work is better than no work.

There is interesting evidence that humans evolved with the intent to work. But it isn’t enough to just work, we need meaning. A story of contribution that makes all this worth it.

When Encyclopedia Brittanica started in 1768, you eventually had hundreds of people updating, tinkering, and re-writing large volumes of information. But with the internet, you could break those large tasks down into smaller ones. In 2005, Jimmy Wales started Wikipedia. A Wiki was a page where anyone can contribute. It didn’t matter if it was just one sentence or paragraphs or whole pages. But anyone can go on there and make an addition. With the help of some volunteers to review and approve changes, you eventually were able to replace Encyclopedias with more up-to-date and more accurate information. This process changed the game forever. For the first time, anyone with a laptop and an internet connection could control the means of production. You had the same access to information as those with all the means. Anyone could now start their own factory. It has only been 15 years, and the game is changing again.

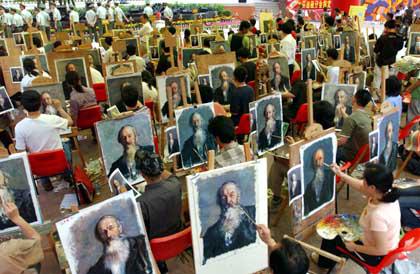

Dafen is a village in China where it is estimated that three-quarters of the world’s oil paintings are produced. If you go there, you will see rows and rows of painters painting the same picture as they did the day before. This isn’t art; this is the industrial act of putting paint on a canvas.

Who makes the art? No one knows. Are they technically proficient? Of course. But art is anything we do as humans that brings emotional labor to the table to make connections. And while we can fool ourselves into this this is art, painting the same thing over and over again with no defects, with no chance for failure–that is industrialism. No humanity, no chance for failure, no art.

Where does the notion of being on someone else’s time come from? It’s quite an unusual phenomenon. For most of human history, time wasn’t a unit of measure. Sure, farmers had seasons to track and a sundial could get you approximate estimates but never precise. To measure the time something took you needed to compare it to something that everyone understood. You can say it the time takes to reach the other side of town by comparing how long it takes to milk a cow or to cook dinner.

One of the greatest challenges to manufacturing production was assembling the masses to show up at the same place at the same time. After all, it didn’t help the assembly line move efficiently if the person at the front was absent delaying the person down the line. Amplifying the problem. You needed factory workers to show up, on time to begin their shift or the whole system could be delayed. The meager pocket watch became a valuable tool.

Before watches were affordable and accurate, you had people whose job was to march the streets and to go around and wake people up. They were called Knocker Uppers, respectively. Knocker Uppers sometimes used Snuffer Outers, long pole that was used for lighting street lamps to tap on the windows of their clients until they woke up. A famous innovator, Mary Smith, used a pea shooter in 1933.

We forget how much has changed as this profession was around until the 1940s and 50s. Time became a commodity. No longer did anyone measure distance by saying it is down the road and it’ll take 4 bowls of rice to get there. Now, you can measure precisely when and where something is. Time was not something we got but what we gave.

There is strong evolutionary evidence that humans developed to naturally want to work.

This makes sense when you think about it.

The way our hand’s developed to hold tools, the way our brains out wired for curiosity. You can also look at what happens to humans, that become isolated with nothing to do—they go insane.

The question then is what type of work?

The type of work with a factory doesn’t give us meaning. And so, it’s this combination of meaning and purpose that drives our work.

We don’t get disgusted at the work ahead when the meaning is important enough.

Achievement doesn’t matter. What matters is effort. When we praise high achievement then there are winners and losers. When we praise effort then we see contributions, we see an arc, we see a journey and not a destination. We create co-dependency relationship when we seek validation. When the awards and accolades don’t come, we think there is something wrong with me. It’s getting harder and harder to compete. Only one first place, only one Nobel. But the warriors journey is long and wide open.

A concept is something we can point to but not touch.

Democracy is a concept. Debt is a concept. An LLC is a concept.

Ideas that we have all agreed upon that now exist but only in the minds of those with the shared vision.

It’s fugazi. No atoms or molecules. It survives only in our minds.

20% of the workforce is part of the caring labor class. These jobs historically were held by women. And largely, left behind. Something that those in power, particularly men, thought it was invisible.

That’s because caring is not measured on a spreadsheet. It isn’t quantified or measured with yields. It one human connecting with another.

As AI continues to replace jobs, many of those who think about the bottom line will start trying to make AI replace what only humans can do.

People care about the story. They care about intent. They don’t need another algorithm.

One common misconception from a historical perspective is thinking about money as some sort of means of exchange used to make bartering easier. We have all heard the story of the neighbor who came over and wanted to buy your cow for 3 goats, but you didn’t want goats so money was introduced as this way to bypass awkward bartering. But what archeology has shown is that there is no evidence in history where this happened. In fact, debt actually came way before money. The first piece of evidence for this is on clay tablets as far back as 2,400 BC Mesopotamia. During the reign of Hammourabi, for instance, there were elaborate debt-keeping systems on tablets that would be destroyed on a periodic basis to wipe the slate clean.

Coins, on the other hand, didn’t start popping up until about 600 BC when major armies were stationed. If you think about it, it makes a lot of sense why this is. If you have an army of say 10,000 soldiers, one of the biggest challenges is figuring out how to feed them. Food that is walking distance of the camp would all be depleted rather quickly, and it would take thousands of people to shuttle the food to the soldiers. It just isn’t a very efficient way to run an army. So, kings eventually figured out that they could take prisoners of conquerers to the mine shafts, dig out pieces of gold and silver, stamp their face on it, voila you have money. You tell the rest of the conquers that you will spare their lives and in exchange you will circulate this money and collect taxes to help finance the war. Historically, not everyone paid taxes, only the conquered. Meanwhile, you pay your soldiers with coins which then can purchase food in the local area and you now have solved the problem of feeding your army.

It’s hard for us to wrap our brains around but imaginary money has been around a long time.